I came across a rather interesting post yesterday entitled The MicroPHP Manifesto. The author made clever use of a very interesting analogy (drum players) to try to prove his point that less is more. The article makes a very interesting read, and I would suggest that everyone reads it. Go ahead. I’ll wait.

With that said, I have to disagree with the article rather vehemently. I think the message is somewhat right, but for all the wrong reasons. Let me try to explain:

The Drummer Analogy

The author uses the analogy of two 1970’s era rock drummers to show his point that more is not necessarily better (in other words, that less can be just as good). On the surface this analogy seems to hold water. However, upon deeper look, it turns out that the very same analogy can be used to disprove the point as well.

The simple fact of the matter is that the two different drummers cited are not equivalent. So comparing the size of the drum sets and determining that the smaller is just as good (or better) is really a bad leap. If you listen to recordings of both drummers, you will see that there’s a HUGE difference in both how they sound, and their contribution to the respective bands. The Black Flag drummers (there were multiple) really just contributed a beat and foundation (rhythm) to the music. On the other hand, Neil Peart contributed much more than that, even at times playing melodies and solos. Comparing the two is really an apples to oranges comparison.

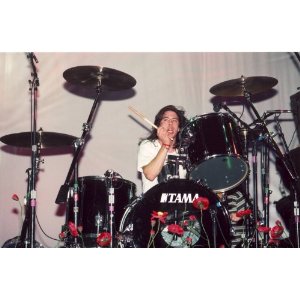

But I said that we can disprove the point with the same analogy. To do so, we just need to look at one drummer: Dave Grohl. He is a very unique drummer from the perspective that he has been the drummer in two popular and vastly different bands (Nirvana and Them Crooked Vultures). If we look at his drum set from Nirvana, we can see that it’s very small and simplistic, which fits in line with the style and feel of the band:

As you can see, the drum set is exceedingly simple. A few drums, a few cymbals, and that’s about it. It fits perfectly with the simple punkish drum style that Nirvana played. But let’s look at his set from Them Crooked Vultures:

There’s a lot more going on here. Sure, it’s not on the Neil Peart level, but it’s distinctly more complicated then the Nirvana drum set. One drummer, two different setups. And therein lies the key.

Hammering a Nail

Let me start off by making a very simple, but very important assertion: different tasks require different tools. Even a task as simple as hammering a nail requires vastly different tools depending on what you’re doing. There are a multitude of different hammers available depending on what the task at hand is:

Sure, you could use the basic carpenters hammer for everything and be done with it. In fact, a lot of amateur carpenters do just that. But the masters, the best at what they do, know that different tasks are best done with the right tool for the job. Would you want to drive a railroad spike with a regular carpenters hammer? Or would you want a proper sledgehammer? Conversely, would you want to drive a finishing nail with the same sledge hammer?

The Right Tool For The Job

The right tool for the job means having multiple tools to choose from. If you know what framework you’re going to use before someone describes the problem that you’re going to solve, you’re doing it wrong. Let me say that again, because it’s important. If you only know one framework, or only use one framework for all problems, you’re doing it wrong.

There are plenty of applications where choosing a full-blown framework like Zend or Symphony is not only overkill, but literally a bad decision. Likewise, there are plenty of applications where not using a full-blown framework would be a bad decision. The key comes down to the specifics of the problem that you’re trying to solve. Are you building a one-off application that’s small and not business critical? Or are you building a flagship application or one that’s going to need to be maintained and expanded over the long term? There are many more questions that go into the decision, but the point is that there’s no one tool that’s right for all jobs. Remember:

If the only tool that you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail…

The “Micro PHP Manifesto”

At the end of the post, the author included a “Manifesto” (akin to the Agile Manifesto). I think it’s worth while going point-by-point to see the good and the bad of it…

I am a PHP developer

Good programmers do not program in their language. They program into their language (term curtsy of Steve McConnell’s Code Complete 2). Programming in a language involves limiting thoughts and implementations to only constructs that the language directly supports. However, programming into a language involves finding the solution they want to do, and then determining how to express those thoughts in the language. When programming in this way, the language stops becoming the limiting factor, and instead becomes just an implementation detail. This is how good programmers are able to be good at multiple languages at the same time. They think above the language…

And that’s why I don’t consider myself a PHP developer. Sure, I write PHP professionally. That’s the language I’ve done most for the past 5 or 6 years. But I consider myself a developer. The fact that I’m doing PHP now is just an implementation detail. Sure, it’s important to understand the limitations and features of the language you’re working with, but in the end that shouldn’t have a huge impact on the final solution.

I like building small things

That’s great! And if all you do is build small one-off products and projects, then that’s fine. The problem comes in that many projects that start off seemingly small very quickly wind up larger than planned. This can happen because of a number of reasons, from business requirements to user demands. It happens often enough that it can’t be dismissed. Just because you’re building small things does not mean you can skip the important step of architecting the solution (In fact, I’d go as far as to say it’s even more critical at that point).

I want less code, not more

While in general I would agree that this is a good goal to strive for, I think it’s a bit misguided here. It fits right along the lines of premature or micro-optimization. Write the code that is needed to solve the problem. Get that code to work (you are using Test Driven Development, aren’t you?). Then and only then try to simplify it. There’s a reason that step 3 in TDD is refactor. It’s not step 1.

In addition, if you’re writing SOLID) code, it will likely be longer than STUPID code. But the key here is not lines of code. It’s not numbers of classes. It’s ease of understanding and maintenance. Maintaining a 10,000 line application that was designed with small classes using SOLID development practices and good naming conventions will be far easier than maintaining even a 100 line application that was built using the STUPID anti-patterns. I care about complexity far more than size. What’s your application’s Cyclomatic Complexity? What’s its CRAP index? (If you don’t know what either of those two are, I’d suggest going and reading up on it)…

I like simple, readable code

I agree on this point. But I find it kind of odd, since it conflicts with the other prior points. Can you have readable code that’s very short and small? Absolutely. But if you’re solving a problem of significance (not a trivial problem), the chances are very good that readable and simple code will be significantly longer than spaghetti procedural code. But that length comes at a very good benefit: understandability.

Human brains are very good at doing a lot of things. However, one thing that they are not good at is keeping a lot of details fresh in the mind. This is why as developers we use abstraction layers all the time. By abstracting a lower level to a very simple API, we are able to not worry about those details, and just worry about the far simpler abstraction. So often the easiest to understand code is code that has many layers of abstraction. That way, when we’re working on a layer, we only need to worry about that layer, and nothing below or above it (in practice, it’s not that simple, thanks to the Law of Leaky Abstractions).

Which method would you rather look at:

public function log($message, $level) {

$f = fopen($this->logFile, 'a');

if (!$f) {

throw new LogicException('Could not open file for writing');

}

if (!flock($f, LOCK_EX | LOCK_NB)) {

throw new RuntimeException('Could not lock file');

}

fprintf($f, '%s [%s] %s - %s', $this->machineName, date('Y-m-d H:i:s'), $level, $message);

flock($f, LOCK_UN);

fclose($f);

}

Or this:

public function log($message, $level = 'notice') {

$message = $this->createLogMessage($message, $level);

$this->file->append($message);

}

I know what my answer is…

Conclusion

I’m not against the micro-framework concept, or that it’s under-rated. In fact, I’ve used Silex before, and like it quite a bit. What I am against is the thought that there is one solution to all problems, or that all problems can be solved by one solution. Every problem is different. The key, and the most important thing of all, is to understand not only what you’re using (framework, libraries, etc), but why that’s the right tool for the job. “Because it’s the one I know best” does carry some weight, but it should never be the driving factor for the solution…