If you’ve been following the news, you’ll have noticed that yesterday Composer got a bit of a speed boost. And by “bit of a speed boost”, we’re talking between 50% and 90% reduction in runtime depending on the complexity of the dependencies. But how did the fix work? And should you make the same sort of change to your projects? For those of you who want the TL/DR answer: the answer is no you shouldn’t.

The Change

The change was adding single line of code:

public function run()

{

+ gc_disable();

That single line of code added caused literally a 90% reduction in runtime. Why?

Well, according to the docs on gc_disable():

Deactivates the circular reference collector, setting

zend.enable_gcto0.

So there you have it. By disabling the collector, speed improved!!!

Yeah, like I was going to leave it at that.

Garbage And PHP

NOTE: This all assumes PHP 5.X. The concepts of this will still be valid in 7, but some of the details may be changed.

PHP uses reference counted variables. That means that copying a variable doesn’t actually copy it internally.

$a = "this is a long string";

$b = $a;

That results in two “pointers” to the same value. Let’s go into C to look at the representation of this.

It’s called internally a zval (Zend Value). And it looks like this:

struct _zval_struct {

zvalue_value value;

zend_uint refcount__gc;

zend_uchar type;

zend_uchar is_ref__gc;

};

Let’s imagine that this is a PHP class:

class Zval {

public $value;

public $type;

public $refcount = 1;

public $is_ref = false;

}

Value is just another data structure that can hold all of the possible values that can be stored. Type indicates which type the value is (defined by the IS_\* definitions. The two interesting values are refcount and is_ref. Let’s talk about them…

So because values aren’t copied internally when you copy a variable, there needs to be a mechanism to make sure that changes go to the correct variable. This mechanism is called Copy-On-Write.

Basically, if you edit a variable who’s value is referenced by more than one variable, it will copy the variable right before modifying it. This makes far more sense with an example, so let’s look at one:

$a = "this is a long string";

Will result in a variable a in a hash table, pointing to a zval instance with a value of string. We can imagine this:

$scope['a'] = new Zval();

$scope['a']->type = IS_STRING;

$scope['a']->value = "this is a long string";

Right now, we don’t need any of those other variables. So far, everything is happy.

But what happens when we copy it?

$b = $a;

Now what? Well, we “point” to the same value:

function copy($scope, $from, $to) {

$scope[$to] = $scope[$from];

}

And thanks to object references, we aren’t duplicating anything! Awesome!

But what happens if we now change one of them? Well, we change both. And we have no way of detecting those changes. So we need to add one.

We need to add another line to that “assignment” (well, two, but we’ll get to the second one in a bit):

function copy($scope, $from, $to) {

$scope[$to] = $scope[$from];

$scope[$to]->refcount++;

}

Great! Now we can detect how many references there are!

Now what?

Let’s now modify one of them. Let’s change $a to another value:

$a = "something else";

Internally, we’d have a check like this:

function write($scope, $var, $value) {

if ($scope[$var]->refcount > 1) {

// reduce the refcount of the original

$scope[$var]->refcount--;

// actually copy the value

$scope[$var] = clone $scope[$var];

// reset the refcount to 1

$scope[$var]->refcount = 1;

}

$scope[$var]->value = $value;

}

So far so good.

There are two more things we need to talk about. The first is references:

$b = &$a;

What happens here, is that we want them to share the same value. So instead of just increasing refcount, we also need to set is_ref to true:

function makeRef($scope, $from, $to) {

if (

$scope[$from]->refcount > 1

&& !$scope[$from]->is_ref

) {

// separate the old one

$scope[$from]->refcount--;

$scope[$from] = clone $scope[$from];

$scope[$from]->refcount = 1;

}

$scope[$from]->is_ref = true;

$scope[$from]->refcount++;

$scope[$to] = $scope[$from];

}

Now, we need to change our write function to not copy if the variable is a reference:

function write($scope, $var, $value) {

if (

$scope[$var]->refcount > 1

&& !$scope[$var]->is_ref

) {

// reduce the refcount of the original

$scope[$var]->refcount--;

// actually copy the value

$scope[$var] = clone $scope[$var];

// reset the refcount to 1

$scope[$var]->refcount = 1;

}

$scope[$var]->value = $value;

}

Now, any writes will be directed to the correct variable. But we still have a problem. We need to fix our copy function, becuase we may accidentally copy a reference!

function copy($scope, $from, $to) {

if (

$scope[$from]->refcount > 1

&& $scope[$var]->is_ref

) {

// Separate it if it is a reference

$scope[$to] = clone $scope[$from];

$scope[$to]->is_ref = false;

$scope[$to]->refcount = 1;

} else {

$scope[$to] = $scope[$from];

$scope[$to]->refcount++;

}

}

If you notice, there’s a fair bit of duplication in there.

Internally, PHP represents these operations as:

-

Always copy the value. This is used when you want to explicitly disable copy-on-write.

SEPARATE_ZVAL_IF_NOT_REF(zval)Copy the value if it’s not a reference. This is what you would call when you’re writing a variable.

SEPARATE_ZVAL_TO_MAKE_IS_REF(zval)Copy the value if it’s not a reference. This is what you would call to make a variable a reference.

The Point

So variables are disconnected from values. This means that deleting a variable (via unset() or falling out of scope) doesn’t delete its value.

So instead, it decrements the refcount (since there is one less variable pointing to it).

Then, it checks to see if the current refcount is 0. If it is, it can safely delete the value, since there is nothing else pointing to it.

This happens internally in zval_ptr_dtor(), which is implemented via i_zval_ptr_dtor:

static zend_always_inline void i_zval_ptr_dtor(zval *zval_ptr ZEND_FILE_LINE_DC TSRMLS_DC)

{

if (!Z_DELREF_P(zval_ptr)) {

ZEND_ASSERT(zval_ptr != &EG(uninitialized_zval));

GC_REMOVE_ZVAL_FROM_BUFFER(zval_ptr);

zval_dtor(zval_ptr);

efree_rel(zval_ptr);

} else {

if (Z_REFCOUNT_P(zval_ptr) == 1) {

Z_UNSET_ISREF_P(zval_ptr);

}

GC_ZVAL_CHECK_POSSIBLE_ROOT(zval_ptr);

}

}

Note that Z_DELREF_P(zval_ptr) is really just a helper that does nothing more than --(zval_ptr->refcount).

There are a few interesting things in here. The first branch happens when the refcount hits zero (meaning there are no variables pointing to it). Once it does, it removes the value from the garbage collector, runs a destructor function, and frees (deletes) it.

The other branch is where things get really interesting. First, it forces the is_ref flag to false if the refcount is 1 (since it’s impossible to reference yourself). This is just an optimization.

But the next line is interesting. GC_ZVAL_CHECK_POSSIBLE_ROOT. What does that do? Well, to understand that, let’s talk about garbage collection.

Two Types Of Garbage Collection

What we’ve described up until this point is known as Reference Counting and is a form of garbage collection. Any time the number of references to a value hits 0, we know we can safely delete it.

The vast majority of situations will be covered completely by this form of GC. This was all PHP had until 5.3.0.

There is a slight problem with it though. It doesn’t handle circular references at all.

Imagine the following code:

function foo() {

$a = array();

$b = array();

$a['b'] = &$b;

$b['a'] = &$a;

}

Internally we have two values created (a and b). But each value has two pointers to it. One for the variable, and one for the array index.

If we were to var_dump($a), we’d see:

array(1) {

["b"]=>

&array(1) {

["a"]=>

&array(1) {

["b"]=>

*RECURSION*

}

}

}

The reason is that we now have what’s known as a Circular Reference.

The problem with it is that with Reference Counting alone, we can never collect that memory again (unless you manually unset one of the array keys).

The reason is that after we delete the two variables ($a and $b) when we leave the function scope, we still have variables pointing to each value (their array keys).

So we would need some way to detect that.

Cyclic Garbage Collection

Enter something called a cyclic garbage collector.

Basically, this is a function which will try to detect those circular references. We call it cyclic, because it’s generalized to not just handle circular references, but handle any kind of Cycle.

So how does it work?

Collecting Cycles

I’m going to describe this backwards. I’m going to talk about how it identifies roots later. From here, let’s talk about how it processes those roots to collect free memory.

PHP has a list (a linked-list) of possible “roots”. These are values that have had their refcount decremented (and hence could be part of a cycle).

Internally, the collector uses a “color code” system to identify states for specific values.

- Black - A normal variable, nothing special

- Purple - A normal variable, but has been marked as a “possible root”, meaning that it may be part of a cycle that’s no longer reachable

- Grey - In process variable, nothing special

- White - In process variable, but can be freed.

They are nothing more than bit flags, but the color system is “easier” to understand.

So when we “collect cycles” (via a few mechanisms, but gc_collect_cycles() as well), we are going to iterate over these roots.

The internal gc_collect_cycles() function does a bunch of things. But there are three lines of critical importance:

gc_mark_roots(TSRMLS_C);

gc_scan_roots(TSRMLS_C);

gc_collect_roots(TSRMLS_C);

It’s a “mark and sweep” algorithm.

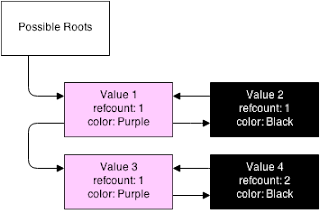

So we start off with our table:

Here, you see that we have 4 values being tracked. Two are on the root buffer (and are purple, both with refcount 1), and two are not (and are black, one with refcount 1 and one with 2). The second object referencing value 4 is not shown (because we can’t get to it, that’s the point).

-

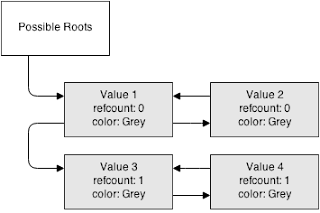

First, it iterates across all of the roots. For each root, it sets the color to grey (in process).

But when it marks it as grey, it then goes deeper into that variable. It iterates through all of the children of that variable, and attempts to mark them as grey as well (if they are not already grey). But when it reaches that child, it reduces the refcount.

So it does a depth-first search through all of the roots and their children, reducing the refcount as it goes (being sure to only reduce it once).

This is basically the same concept as “if this root were to be removed, what would happen to the rest of the children”.

It does this for the entire variable graph.

As you can see, all of the refcounts are decremented by one.

-

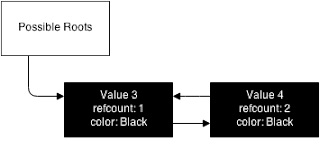

At this point, it will do another depth-first search through all of the roots and their children. This time, it checks to see the refcount (assuming that the color is “grey” - in-progress).

If the refcount is more than 0, it means that there must exist another reference to it. So it’s set to black (meaning that it’s a normal variable) and every child is also set to black.

If the refcount is 0, then that means that there’s a cycle. The value is set to white meaning it can be marked for removal.

After the scan, all of the colors should be either black or white. Meaning still have references, or don’t.

In this case, both values 1 and 2 are marked for collection.

-

Yet another depth-first search through all of the roots and their children. Except this time, any white values are collected and freed.

Non-white values are skipped (nothing happens to them).

As you can see, values 1 and 2 are gone.

Notice what happened there. We did a depth-first search through every value in the graph. But not only that, we did three.

You may spot something that could be fixed. You could say, why not combine the scan and collect phases into one pass?

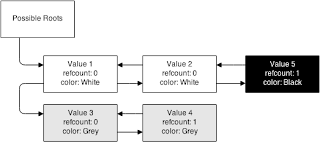

Well, there’s a problem. If you had a complex relationship, where there are more than 2 elements in the graph, you wouldn’t be able to do that:

This is mid-scan. We’ve already marked value 1 and 2 as white, since their refcount is 0. But then we come to value 5. Its refcount is 1, meaning there’s still a reference to it.

So now, we’re at a dilema. If we freed as part of scan, we’d have deleted information we need. But in this case, we can just search right back and mark value 2 as black (since a parent is black). So the overall graph would wind up black in the end.

So this is not a cheap thing.

Collecting cycles takes a lot of power to do. It is especially expensive on object graphs that are deep, since it needs to visit every object.

Suffice it to say it’s an expensive operation.

Thankfully it happens extremely infrequently in normal applications. And when it happens, it’s likely because you’re allocating a lot of objects, and hence can have a lot of cycles built up (and hence a chance to save a lot of memory).

So that’s how we collect roots. Let’s talk about how we find them.

Finding Possible Roots

Well if you remember back to the zval_ptr_dtor call, there was a call to GC_ZVAL_CHECK_POSSIBLE_ROOT at the end. That macro proxies to gc_zval_check_possible_root():

static zend_always_inline void gc_zval_check_possible_root(zval *z TSRMLS_DC)

{

if (z->type == IS_ARRAY || z->type == IS_OBJECT) {

gc_zval_possible_root(z TSRMLS_CC);

}

}

So basically, if the type is complex (can have child variables), then say that it’s a possible root (meaning that it may be the source of a cycle). So it runs a root algorithm.

A lot is going on here, but basically it boils down to a few basic steps:

Check to see if it’s already a root

if (GC_ZVAL_GET_COLOR(zv) != GC_PURPLE) {So this if statement basically says “if this value is already a root, skip it”.

If it’s not a root, make it one.

To make it a root, first we set the color to Purple:

GC_ZVAL_SET_PURPLE(zv);This is just really house-keeping, and doesn’t really effect anything.

Then, we need to check to see if we’ve already stored this in the list of possible roots:

if (!GC_ZVAL_ADDRESS(zv)) {This again is house-keeping. In practice, we can ignore this part since it should never get out of sync with the Purple flag. This is here as protection.

The next bit is where interesting things start happening:

So the GC uses a linked list for the buffer of possible roots. So to add a root, we need to get the next unused item (the head of the linked list).

I’ll explain inline:

gc_root_buffer *newRoot = GC_G(unused); if (newRoot) { GC_G(unused) = newRoot->prev;If we get back a “unused memory block” from the buffer, that means that we’ve already added and removed an item from the GC buffer. So since we have a free slot, we can just add it straight away.

} else if (GC_G(first_unused) != GC_G(last_unused)) { newRoot = GC_G(first_unused); GC_G(first_unused)++;We have free space in the buffer that we haven’t used, so add it there.

} else {This happens when our root buffer is full. By default, the root buffer is allocated to be 10,000 values.

if (!GC_G(gc_enabled)) { GC_ZVAL_SET_BLACK(zv); return;Well, if GC isn’t enabled, then why bother at all…

} zv->refcount__gc++;Remember we decremented the refcount earlier. We need to increment it here before the run, since the run will try to decrement it again.

gc_collect_cycles(TSRMLS_C);Collect the cycles to try to open up space.

zv->refcount__gc--;Restore the refcount to what it was.

newRoot = GC_G(unused); if (!newRoot) { return;So this means that our root buffer is full. Meaning that we’ve already got 10,000 values that we’re tracking as part of possible cycles. So since we have no more room, rather than re-allocating, we just return.

} GC_ZVAL_SET_PURPLE(zv); GC_G(unused) = newRoot->prev; }This means we’ve found a spot, so we’re going to add it.

Do some house-keeping

newRoot->next = GC_G(roots).next; newRoot->prev = &GC_G(roots); GC_G(roots).next->prev = newRoot; GC_G(roots).next = newRoot; GC_ZVAL_SET_ADDRESS(zv, newRoot); newRoot->handle = 0; newRoot->u.pz = zv; GC_BENCH_INC(zval_buffered); GC_BENCH_INC(root_buf_length); GC_BENCH_PEAK(root_buf_peak, root_buf_length);The rest of this is just some house-keeping. Nothing really important happens here for our concerns, this is just the actual mechanics for adding the value to the root buffer.

Did you notice the problem?

If not, go back and look through the code carefully. See if you can spot it.

What Happened To Composer

Composer includes a SAT Solver. Basically, it’s a graph of requirements, that it then solves by looking at combinations of dependencies that satisfy the requirements. It’s quite smart in how it does it, but it’s a lot of operations and is by no means a trivial problem.

But one of the ways it solves this problem is by creating objects. A lot of objects. Like an extreme amount. Potentially tens or hundreds of thousands of them. Or more. Some with circular references.

Now, remember how an object gets put on the root buffer. It just needs to have its refcount decremented.

It can happen if you unset a variable:

$a = $obj;

unset($a);

Or if you call a function:

function foo(StdClass $foo) {

}

foo($obj)

When the object is passed in, its refcount goes up. When it leaves the function, it goes down and hence gets added to the list of possible roots.

So objects are added to the root buffer all the time. This is quite quick under normal situations and has little to no performance impact.

However, there was a hint above as to the problem:

When the root buffer is full, it will try to run the gc_collect_cycles() function to free up space.

There is room for 10,000 entries in the root buffer.

That means that if you’ve got more than 10,000 objects that have their refcounts decremented, it will try to collect cycles every single time a new one’s refcount is decremented.

It’s important to make this one point clear:

It’s not enough to make 10k objects. You’d need to decrement without collecting all 10k objects. This is fairly rare.

$array = [];

for ($i = 0; $i < 10000; $i++) {

$array[] = new StdClass;

}

Would not result in any objects on the root buffer. Because the individual objects aren’t decremented (only the array is).

You’d need to pass every object to a function individually:

foreach ($array as $value) {

doSomething($value);

}

This happens. A lot. But with 10k objects in a single execution (at the same time), it’s not exceptionally common. And it’s not happening in most web requests.

The Take Away

Don’t go adding gc_disable() to all of your code. What happened here is a pretty rare event. They created a ton of objects that they needed, and kept using. This triggered an edge-case situation where it kept calling the garbage collector over-and-over.

For Composer, disabling garbage collection prevented them from running into this situation. This helped them. But more often than not, the GC is actually quite smart. More often than not, it’ll be better for you than not running it.

My argument is that if you’re running into performance issues, you can try disabling garbage collection. But don’t leave it off.

If it makes an improvement, fix your application. There are very few problems that require creating and keeping alive 10k objects. Especially in a web request You are far more likely to be better served by an algorithm change than by just blindly disabling a system that on the whole is quite good. So fix your code, don’t just band-aid it. (SAT solving, and graphs in general are one case where you really do need that many objects).

This also shows that some improvement to the garbage collector can be done. Rather than running the collection cycle on every attempt to add a new root past 10k, perhaps a better algorithm could be developed. A few options:

Exponential back-off

In this case, you’d try running the collector. If it failed, you’d increment a counter.

Before trying the next run, you check to see if the counter is an even power of 2. If it is, run the collector. Otherwise, skip the run.

if (0 == (GC_G(collect_counter) & (GC_G(collect_counter) - 1))) { // only run on even-power-of-two calls, 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc zv->refcount__gc++; gc_collect_cycles(TSRMLS_C); zv->refcount__gc--; } newRoot = GC_G(unused); if (!newRoot) { // increase counter, as it's a failed run GC_G(collect_counter)++; return; } // reset counter to 0 GC_G(collect_counter) = 0;This works nicely, since it will still keep trying to collect, but it will do it less and less frequently if it’s shown to not be effective.

And if a collection is ever successful, it’ll run again next time it gets full (maximizes usefulness).

Increase the buffer size on failed collect run

Here, we’d re-allocate the buffer from 10k to 20k if the run failed.

This can get EXTREMELY expensive for large numbers of objects, since it increases the runtime of the collector operation.

Run the collector on a probability basis

Define a config option for how often to run the collector. Similar to session garbage collection. Then if the buffer fills, only run the collector with that probability.

Another idea?

But that’s what really happened.